Disproving locality and realism with quantum computers

The principle of locality means that objects can only interact with and be affected by other objects in their immediate, local surrounding. The principle of realism, on the other hand, says that objects have definite properties. In other words, the outcome of a measurement would be defined before a measurement is actually performed. Sound principles of physics, it would seem. Our current understanding of quantum mechanics indicates, however, that it violates realism, locality, or both. Here, we conduct an experiment that puts the quantum mechanical view of our universe to the test.

Einstein, who won his Nobel Prize for his fundamental discoveries in quantum physics, contended with this fact. He famously called quantum entanglement Spukhafte fernwirkung, “spooky action at a distance”. In 1935, together with two colleagues, he published a paper arguing that the quantum mechanical description of reality was fundamentally incomplete as it allowed, among other things, measurements of one system to affect the reality of another. “No reasonable definition of reality could be expected to permit this”, argued Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen [1]. Instead, Einstein proposed that so-called hidden variables could fully describe quantum mechanics. These hidden variables, features, of systems could perhaps be inaccessible to us even in theory, but would nevertheless get rid of the “spookiness” of quantum mechanics and re-establish a deterministic universe.

30 years later, John Stewart Bell would show that contrary to Einstein’s opinion, quantum physics does violate certain constraints that any local hidden variables would impose on independent measurements [2]. The first experimental verification of Bell’s theorem was published in 1972 [3]. The 2022 Nobel Prize for physics was awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger in large part for their experiments verifying Bell’s reasoning. Now, with the advent of quantum computers, we can perform this experiment from our home laptop!

CHSH inequality

An experiment that tests the constraints that John Bell presented is known as a Bell test. In this experiment, we conduct one of the various Bell tests, namely the CHSH inequality, named after its authors, Clauser, Horn, Shimony, and Holt [4]. It consists of two particles, for each of which two different measurements can be performed. By combining multiple different measurement outcomes of the two particles, we can formulate a quantity that has a strict bound, such that no results should be able to exceed it. We can, in fact, define many quantities of this form, although in this case we only observe two, which we shall call CHSH1 and CHSH2.

The constraints for the CHSH inequality originate from two main assumptions. First is the assumption of locality, the principle that interactions cannot propagate faster than light. This rule comes from Einstein’s theory of relativity, which establishes the speed of light as the ultimate speed limit in the universe. Consequently, if anything were to travel faster than light, it could disrupt the relationship between cause and effect. In the experiment, this assumption means one particle’s measurement cannot instantly affect the other’s measurement.

Second, there is the assumption of realism, the notion that the measurements show real properties of the object that exist independently of the action of measurement. Put simply, physics does not depend on the role of an observer. This principle becomes problematic with quantum phenomena. For instance, in the double-slit experiment, particle behaviour appears to change when observed. The hypothesis was that there existed a complete description of quantum theory where the real properties of the system were described by hidden variables missing from the theory.

In truth, the CHSH inequality says nothing about the workings of quantum mechanics; it only predicts possible results of systems following the assumptions of realism and locality. Two seemingly reasonable assumptions for systems observed in nature.

Experiment

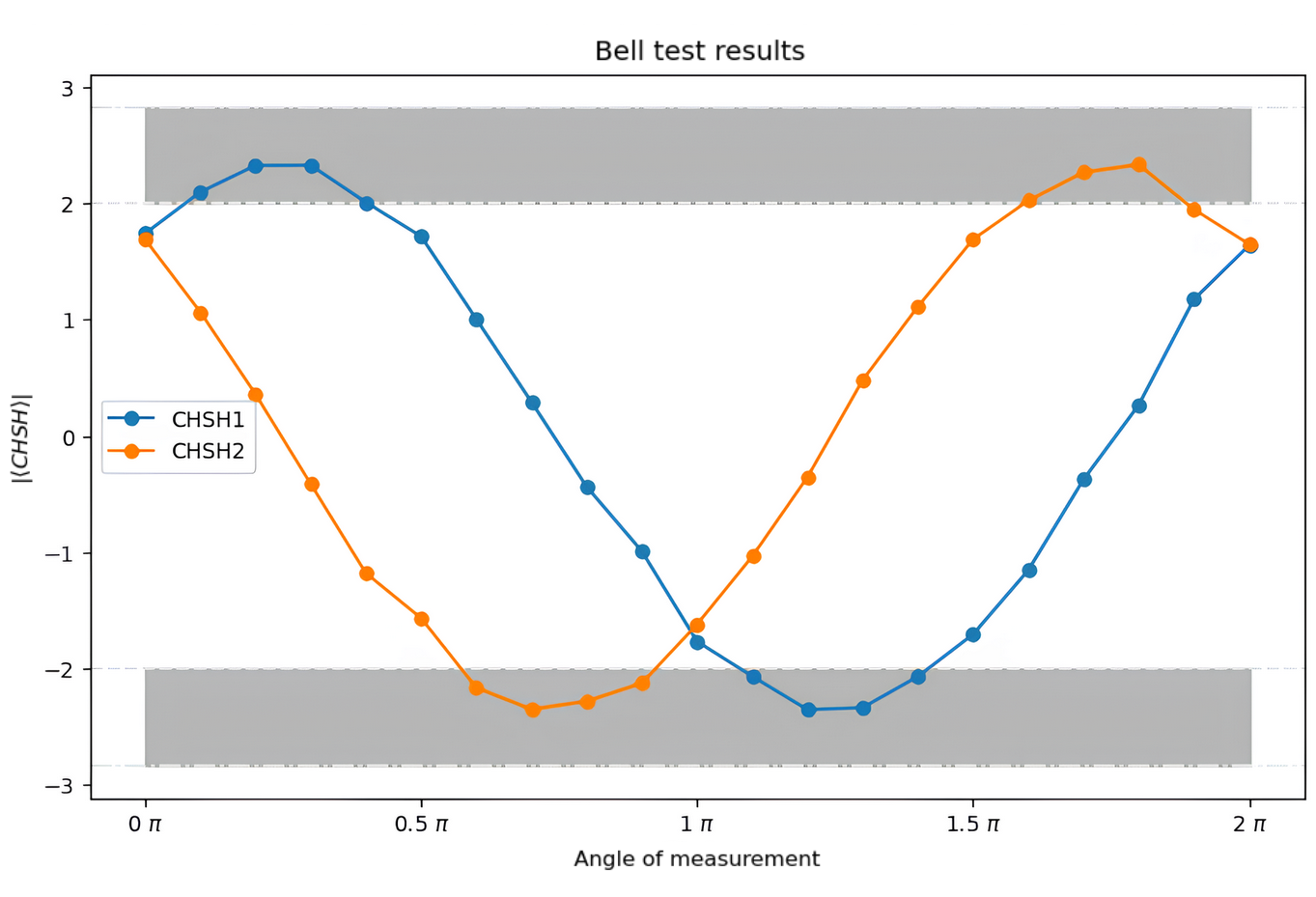

This section delves deeper into the technical details of the experiment. The impatient can skip to the results of the experiment, shown in Figure 3. The exposition is based on the IBM tutorial on the CHSH inequality [5].

The aim of the experiment is to attain values for CHSH1 and CHSH2. To achieve this, we need to measure every combination of measurements for the two systems, in this case, qubits. The individual measurements can only result in +1 or -1, and the results are summed such that the total can at most add up to 2.

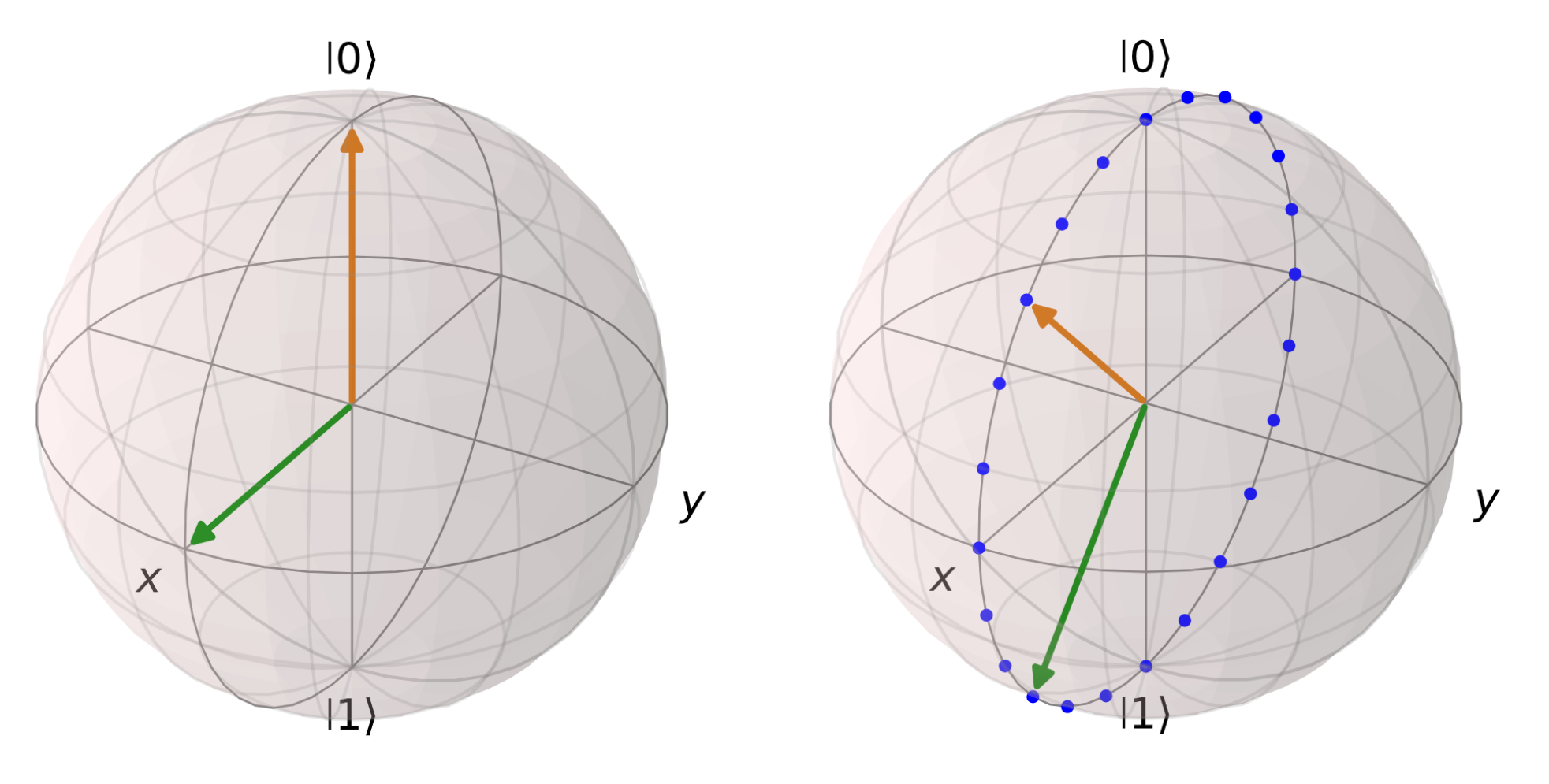

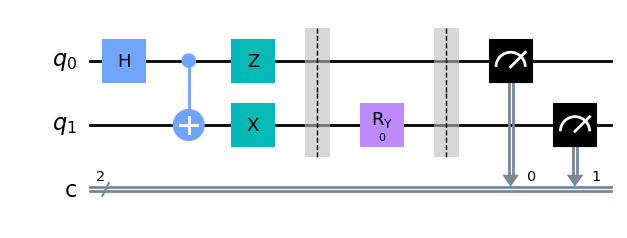

First, we prepare two qubits in a state that is maximally entangled. Entanglement is a uniquely quantum behaviour where the state of one particle is inseparably linked to the state of the other. The entanglement is created by applying a quantum logic gate that applies an operation to one qubit depending on the state of the other qubit. For the first qubit, the chosen measurements are the X and Z properties. For the second qubit, the measurements are chosen such that the relative angle of the two measurements is maintained, but the measurements themselves are rotated over the Y-axis.

Figure 1: A qubit’s state can be plotted on a sphere. The orange and green lines correspond to the chosen measurements. For the first qubit, shown on the left, these measurements are fixed. For the second qubit, these measurements are rotated throughout the Y-axis, and measurements are taken for each dot pictured

As a result, we measure a combination of both physical properties for the second qubit. Using these measurements, we compute values for each possible combination of outcomes. We then combine these results to obtain the final values for CHSH1 and CHSH2.

Figure 2: The complete quantum circuit for measuring the qubits. The first section corresponds to preparing our qubit in a maximally entangled state. In the second section, the angle of measurement for the second qubit is varied with a rotation over the Y-axis. In the last section, we perform a Z measurement

The Bell test experiment was conducted on the Helmi quantum computer through the Finnish Quantum-Computing Infrastructure (FiQCI). The results of the experiment are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The values of CHSH1 (blue) and CHSH2 (orange) at different angles of measurement. The boundaries for results following local hidden variables are marked by a dotted line. The area shaded grey denotes the realm of quantum correlations surpassing classical bounds, thus violating the Bell inequality

Results and Outlook

As the experiment reveals, quantum results do indeed exceed the bounds for systems following local hidden variables, as was theoretically predicted by John Bell in 1965. Since our assumptions of locality and realism contradict our results, it means that either or both assumptions are incorrect. This illustrates the unintuitive nature of the quantum world, where effects propagate faster than light, and the act of measuring something creates the result. Notably, entanglement, a hallmark of quantum mechanics, plays a pivotal role here, as entanglement is the very reason why the classical bounds can be exceeded. This shows the potential for quantum technologies, which, as shown here, can exceed classical possibilities.

While current quantum computers are still in their infancy, both in technological maturity and computational capacity, their utility extends beyond algorithmic computation. Quantum computers prove invaluable for conducting experiments in fields like physics and chemistry. Quantum simulations bridge the gap between experimentation and simulation, effectively conducting quantum experiments on quantum processors. This remarkable potential opens doors to unprecedented exploration and understanding of quantum phenomena and their macroscopic effects.

Notebooks

The Jupyter notebooks for conducting these experiments in fundamental physics, delving deeper into the details of the Bell tests, can be executed directly on the FiQCI infrastructure. They are available for download here: https://github.com/CSCfi/Quantum/tree/main/Bell-tests

References

- 1. A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, N. Rosen, “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?”, Physical Review 47 (1935) 777-780

- 2. J.S. Bell, “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox”, Physics Physique Физика 1 (1965) 195–200

- 3. S.J. Freedman, J.F. Clauser, “Experimental Test of Local Hidden-Variable Theories”, Physical Review Letters 28 (1972) 938–941

- 4. J.F. Clauser, M.A. Horne, A. Shimony, R.A. Holt, “Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories”, Physical Review Letters 23 (1969) 880–4

- IBM, “CHSH Inequality” (accessed 18 June 2024)

Give feedback!

Feedback is greatly appreciated! You can send feedback directly to fiqci-feedback@postit.csc.fi.