Simulating electrons is an important but challenging task in condensed matter physics and material science. Simulation of electronic models, such as solving the ground state energy of the Fermi-Hubbard model, is expected to be among the first non-trivial problems to demonstrate quantum advantage on near-term quantum computers. Here, the leading approach to solving this problem, a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm called the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is explored. We present results from running the hybrid algorithm using the LUMI supercomputer and the VTT Q50 quantum computer and share benchmarking results on how circuit choice and compiler selection impact performance. In addition, we demonstrate the implementation of error mitigation strategies to improve results.

Why Quantum Computing for Simulating Quantum Systems?

Quantum systems such as electrons exhibit complicated behavior, which is notoriously difficult to simulate on classical computers. Quantum systems can be in multiple states simultaneously before measured, a property called superposition. Further, their states can be strongly correlated over large distances, a property called entanglement. For simulating such a system, the information that needs to be stored scales exponentially, quickly becoming impossible for classical computers to handle. Even the most powerful classical supercomputers can only simulate relatively small quantum systems. This has hindered progress in some important areas such as high-temperature superconductivity. Quantum computers, on the other hand, inherently leverage quantum phenomena to encode and store information, which makes them naturally suited to simulating quantum systems [12].

Modelling Electrons: The Fermi-Hubbard Model

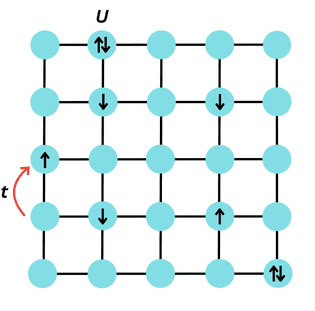

The Fermi-Hubbard model describes fermions, such as electrons, in a solid. In the model, the behavior of electrons in a solid is represented by a lattice where the electrons can hop between lattice sites [1, 2, 3, 4]. The electron interactions include a repulsive on-site interaction $U$ and a kinetic energy $t$ that allows the electrons to move around. The ratio between the repulsive interaction and kinetic energy, $U/t$, determines the electron distribution over the lattice sites [3].

Figure 1: An illustration of the two-dimensional Fermi-Hubbard model showing a lattice of 25 sites. The arrows represent electrons, with spin either up or down. Each site can be either unoccupied, singly occupied, or doubly occupied by two electrons with opposite spins.

The ground state energy of such a system can be calculated using classical computers only for small system sizes. For larger systems, containing more than some dozens of lattice sites, finding the ground state energy becomes too complex for classical computers to handle directly [2]. For more details on why this happens, check out the blog post on classical simulation of quantum systems here. Even as a simplified model, the Fermi-Hubbard model captures many interesting phenomena of real solids, such as high-temperature superconductivity, quantum magnetism, and metal-insulator transitions. It has therefore become a paradigmatic model for strongly interacting electrons [3].

While quantum computers are naturally suited for simulating quantum systems, electrons are not as straightforward to simulate. This is because electrons obey different statistical properties than the qubits in which the information is encoded. Hence a mathematical transformation is required to move between the two frameworks, called fermion-to-qubit encoding [6]. Different mappings exist – in this project, we use the Jordan-Wigner transformation. In this mapping, the number of qubits needed is twice the number of electron lattice sites to be simulated: $2N$ qubits for $N$ electron sites.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver

While the simulation of quantum systems is a promising application of quantum computing, current quantum computers have a limited number of qubits available, and noise poses constraints on circuit depth. Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have been designed to overcome these limitations and have therefore become a leading approach in attempting to reach quantum advantage with current and near-term so-called Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [5].

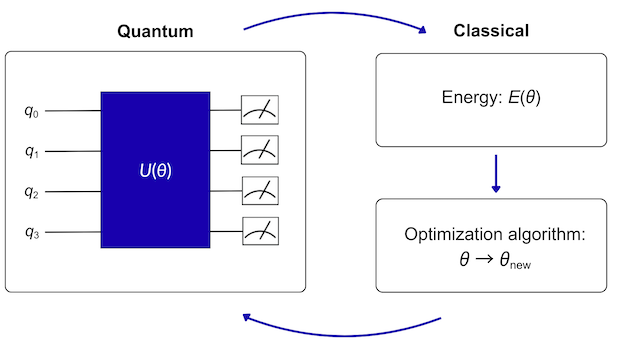

VQAs leverage a learning-based approach, where a parametrized quantum circuit is run iteratively on a quantum computer, and the circuit parameters are optimized in a classical optimization loop. This approach has the benefits of keeping the circuit depth shallow and being somewhat more resilient to noise. Essentially, VQAs can be considered a quantum equivalent of classical machine-learning methods, with a structure similar to neural networks [5].

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) in particular is designed for the task of finding the ground state energy of a quantum system, an important problem in applications such as drug design and material science. The cost function in a VQE is the energy of the system, which is iteratively minimized in the classical optimization loop until the final ground state energy is (hopefully) achieved. The parametrized quantum circuit defines the search space or the family of quantum states that the optimization can explore [9].

Figure 2: An illustration of the structure of a Variational Quantum Eigensolver. The quantum circuit is iteratively executed on a quantum computer, and the circuit parameters $\theta$ are updated each time using classical post-processing within the loop.

Benchmarking Quantum Circuits

The choice of quantum circuit is particularly important in Variational Quantum Algorithms, as the classical optimisation part is itself a computationally hard problem and will likely fail unless the circuit is carefully designed in a problem-specific way [10, 11]. This is crucial for preventing two common problems with the optimization landscape of variational algorithms: local minima, which cause the optimizer to get stuck in suboptimal solutions, and barren plateaus caused by vanishing gradients [10].

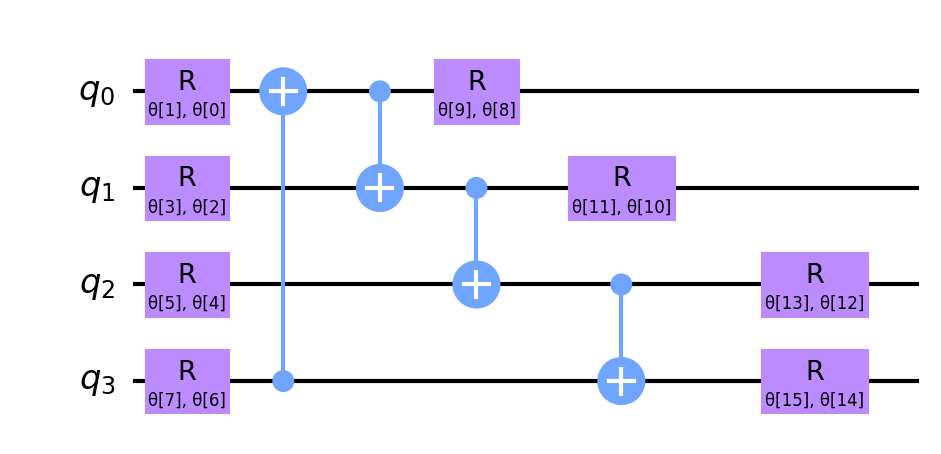

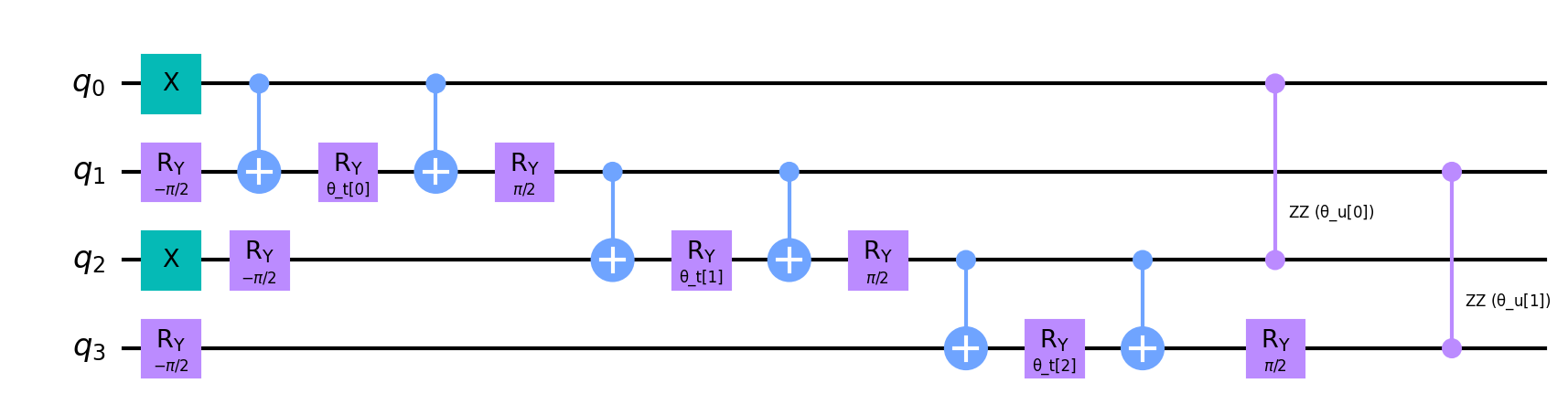

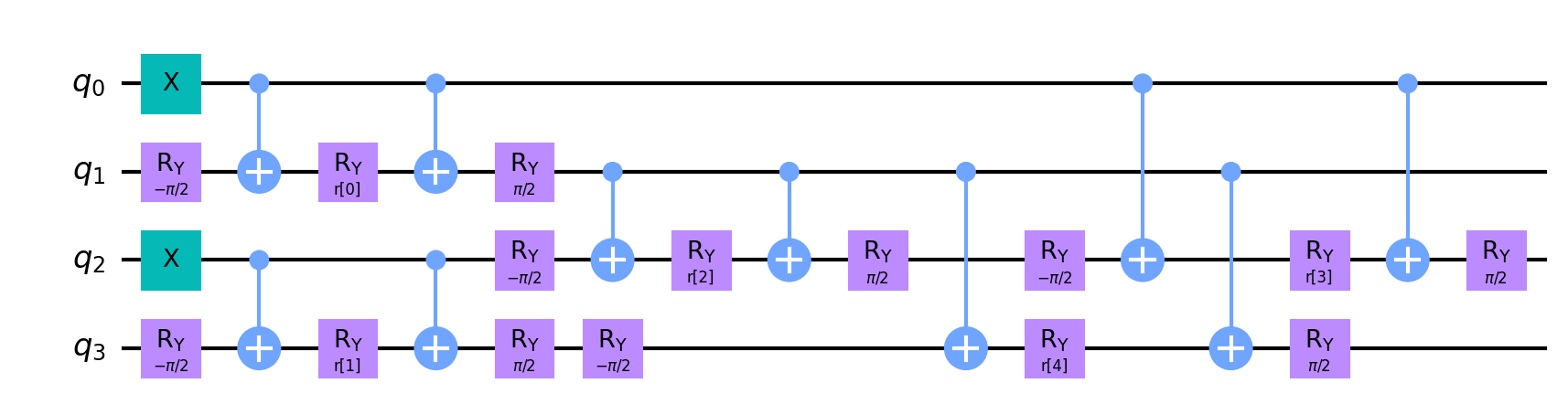

Here, a comparison of three different circuit options for the Fermi-Hubbard model VQE was made: the hardware efficient EfficientSU2 circuit, the Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) which is commonly used for the Fermi-Hubbard model, and a custom physically-inspired fermionic circuit developed in this work. Additionally, all three of these were tested with an extra number-preserving (NP) layer to increase expressibility.

Figure 3: The hardware efficient EfficientSU2 circuit.

Figure 4: The Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz.

Figure 4: The Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz.

Figure 5: The physically-inspired fermionic circuit.

Figure 5: The physically-inspired fermionic circuit.

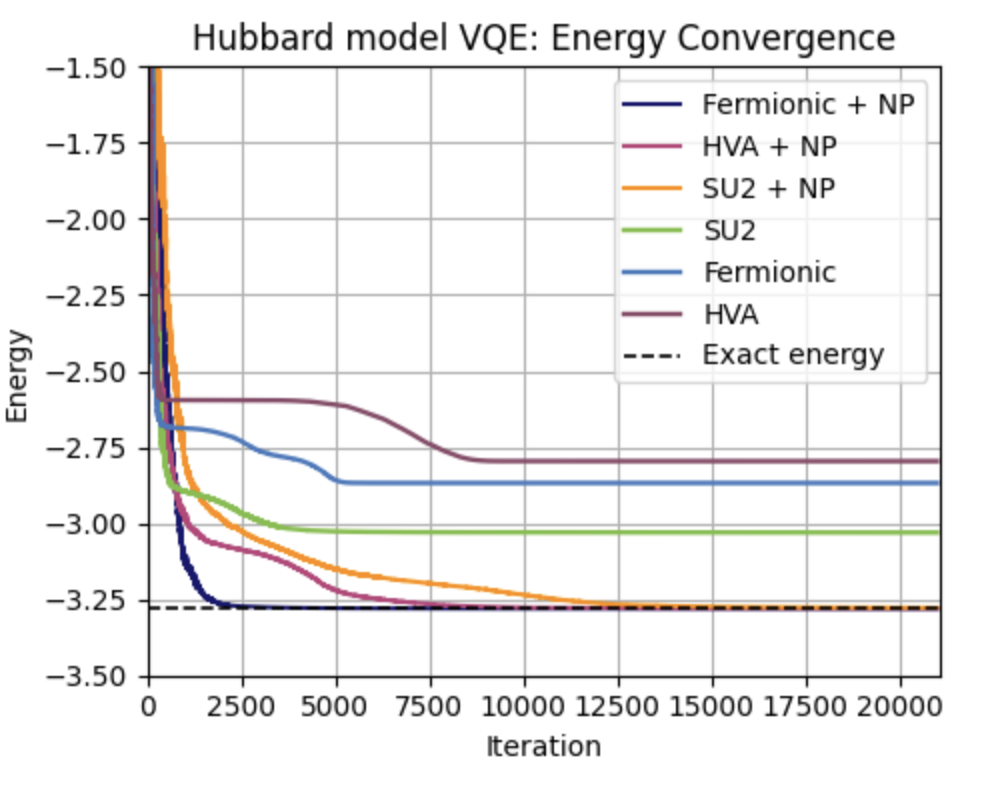

From Figure 6 below it can be seen that the fermionic + NP, HVA + NP and SU2 + NP circuits perform best, reaching the correct ground state energy in noiseless simulation. However, while the hardware-efficient SU2 + NP circuit predicts the energy accurately for small numbers of qubits, it does not respect the physical symmetries of the system (conservation of particle number and spin) and fails to scale to larger models. The Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA + NP) and the custom physically inspired fermionic circuit (fermionic + NP) also respect the symmetries of the system. Therefore, the best performing parametrized circuits were found to be the fermionic + NP circuit and the HVA + NP circuit. Both reach the correct ground state energy with a good accuracy, scale to larger systems, and respect the physical symmetries of the Fermi-Hubbard model.

Figure 6: A comparison of the performance of different parametrized quantum circuits in finding the ground state energy of the Fermi-Hubbard model. Each circuit has 6 qubits. A noiseless simulator together with the BFGS optimizer has been used.

Benchmarking Compilers

Due to the variability in native gatesets and qubit connectivity across quantum computers, circuit compilation is a necessary step before executing a quantum circuit on a real quantum computer. This process maps a quantum circuit to the specific architecture of a target device. To guide the selection of an optimal compiler, a comparison was made of four different compilers:

- Qiskit’s transpiler

- Berkeley Quantum Synthesis Toolkit (BQSKit)

- TKET

- Unitary Compiler Collection (UCC).

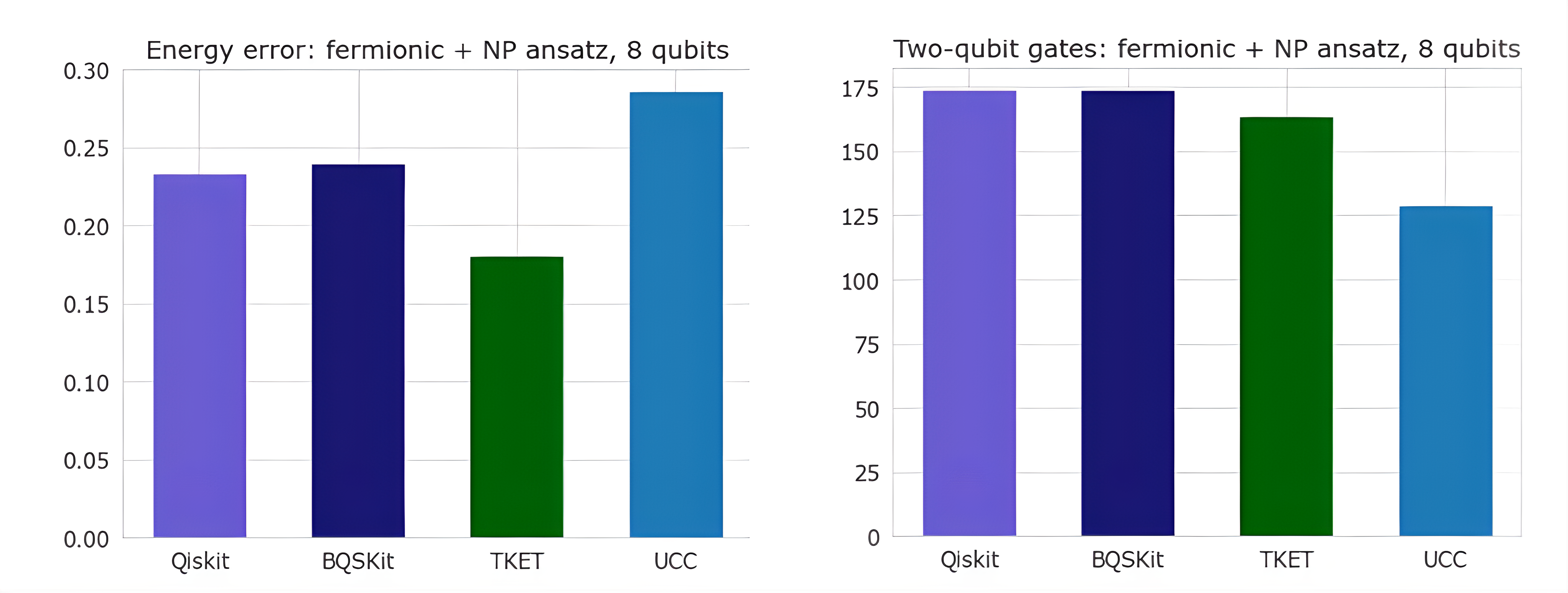

Figure 7 compares the performance of these compilers for our specific problem.

Figure 7: Comparisons of energy error and two-qubit gate count for different compilers, obtained from noiseless simulation.

Comparing the energy error given by the different compilers, TKET gave the smallest energy error and therefore was the best in terms of energy accuracy. On the other hand, comparison of two-qubit gate count shows that UCC results in the lowest number of two-qubit gates. Given that two-qubit gates are a significant source of error in many current devices, the UCC compiler is likely to perform best on imperfect hardware.

Fermi-Hubbard VQE Results on VTT Q50

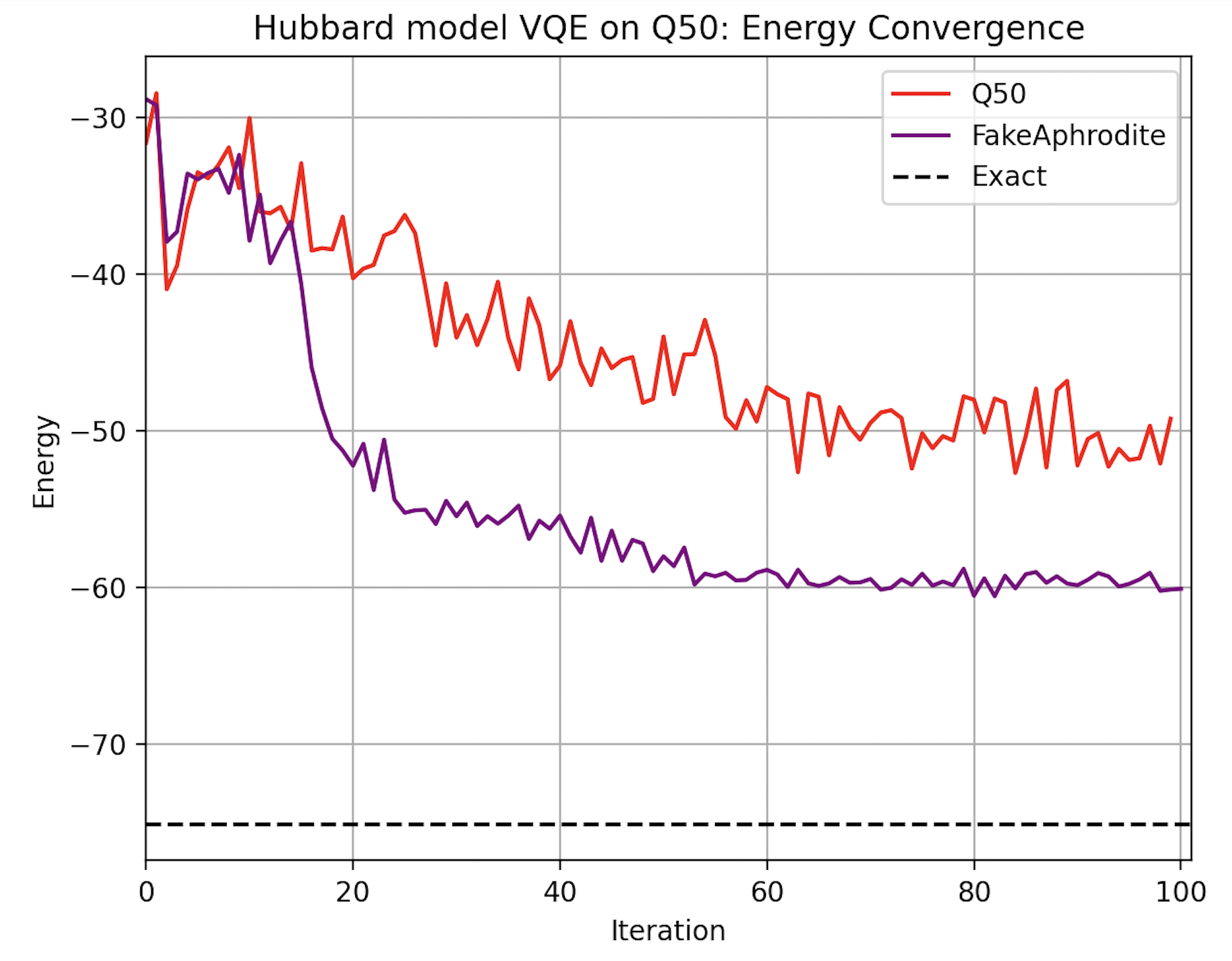

The VQE for the Fermi-Hubbard model was run on the VTT Q50 quantum computer using 6 qubits. Figure 8 shows a comparison of the energy convergence and thus ground state energy achieved on a real quantum computer (VTT Q50) and noisy simulator (FakeAphrodite). When running on the real quantum computer, the SPSA optimizer was used as it performs the best with noise.

Figure 8: VQE energy convergence on a real quantum computer (VTT Q50) and noisy simulator (FakeAphrodite).

From Figure 8 it can be seen that on the real quantum computer, the energy converges but not to the correct ground state energy, due to the large amount of noise present on the real device.

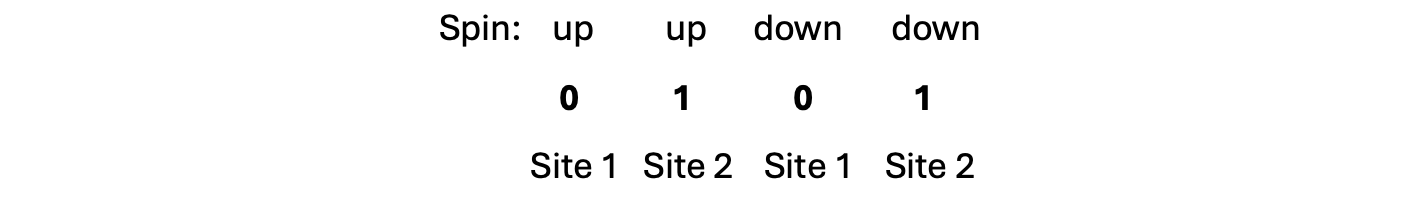

In addition to the ground state energy, the VQE gives the occupation states of the system, or the distribution of the electrons in the lattice. The states obtained from the VQE following the fermion-to-qubit transformation encode the occupation states of the electron lattice model as follows, taking one state of the 2-site chain as an example:

Figure 9: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at low $U/t$ ratio, showing nearly equal distribution over states with double occupancy (0101 and 1010) and antiferromagnetic states (0110 and 1001).

Figure 9: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at low $U/t$ ratio, showing nearly equal distribution over states with double occupancy (0101 and 1010) and antiferromagnetic states (0110 and 1001).

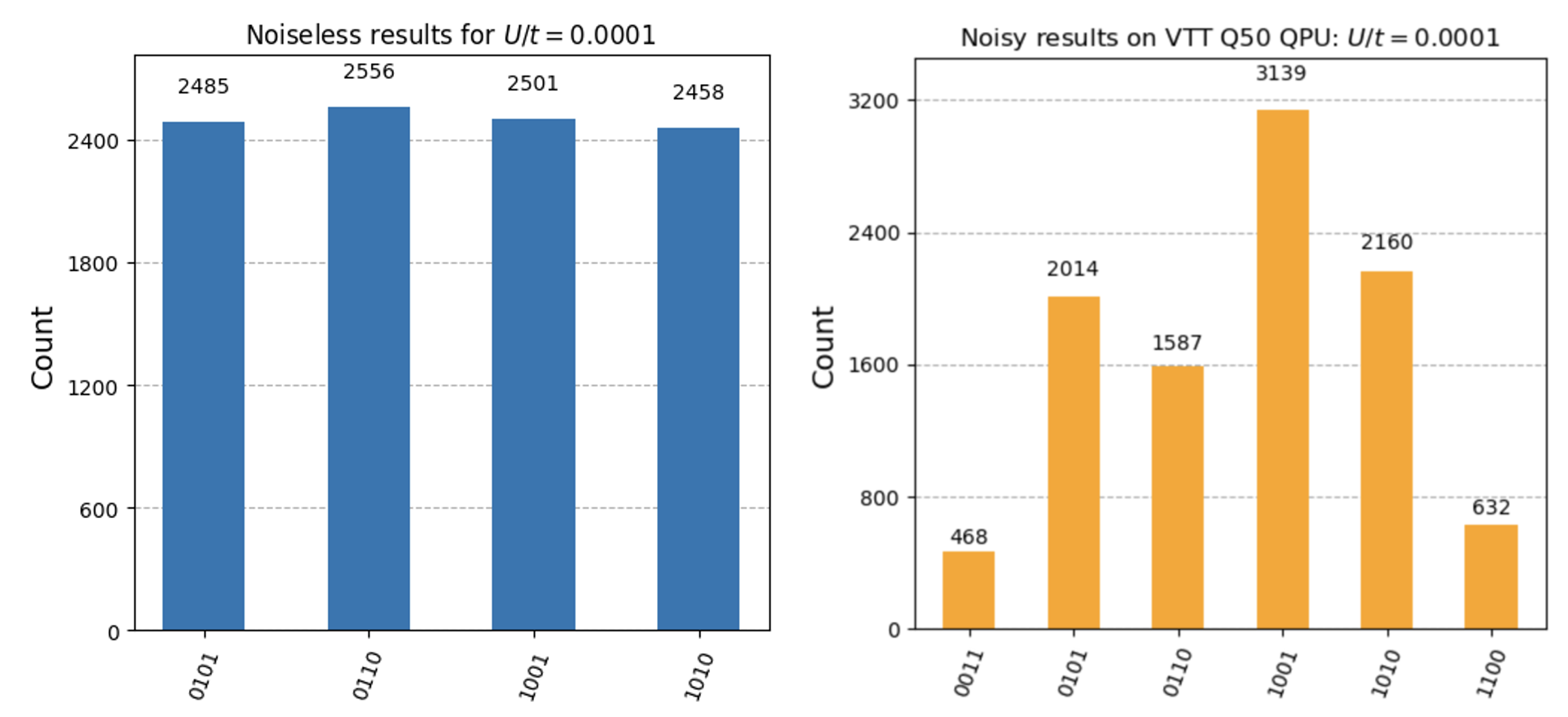

Figure 10: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at intermediate $U/t$ ratio, showing decreasing double occupancy.

Figure 10: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at intermediate $U/t$ ratio, showing decreasing double occupancy.

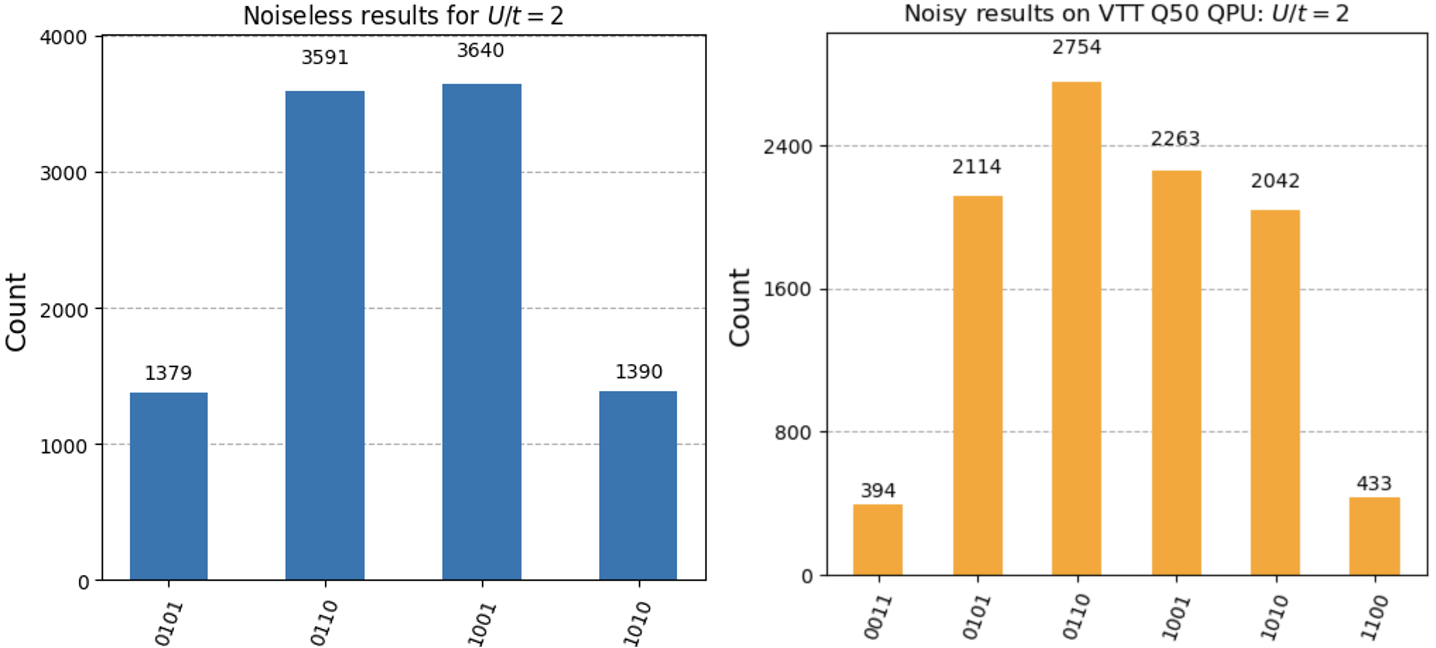

Figure 11: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at a high $U/t$ ratio, showing vanishing double occupancy and a strong preference for antiferromagetism. The system at high $U/t$ ratio is highly entangled and therefore more difficult to simulate, as shown by the appearence of the states 0011 and 1100 in the noiseless results, which are nonphysical at half-filling.

Figure 11: Results obtained from noiseless simulation (left) and the VTT Q50 quantum computer (right) for the half-filled 1D Fermi-Hubbard model at a high $U/t$ ratio, showing vanishing double occupancy and a strong preference for antiferromagetism. The system at high $U/t$ ratio is highly entangled and therefore more difficult to simulate, as shown by the appearence of the states 0011 and 1100 in the noiseless results, which are nonphysical at half-filling.

Each lattice site in the Fermi–Hubbard model can be empty, singly occupied (one electron), or doubly occupied (two electrons with opposite spins, as required by the Pauli exclusion principle). At half filling, the model captures Mott insulating behavior. For small $U/t$ (weak interactions), the repulsion between electrons is small compared to their kinetic energy, so double occupation is common: one spin-up and one spin-down electron can occupy the same site. As $U$ increases, however, double occupation becomes energetically costly, and the system favors configurations that avoid it. At large $U/t$, double occupancy is strongly suppressed, and the ground state instead exhibits antiferromagnetic order [3].

Figures 9, 10 and 11 show that the results obtained from VTT Q50 correctly capture this trend.

Error Mitigation Strategies

Current and near-term quantum computers are hindered by noise, which is a major obstacle to obtaining useful results. To address this, many different error mitigation techniques have been developed to combat specific kinds of errors [8]. Here, two such strategies have been implemented: post-selection to discard non-physical results and readout error mitigation to compensate for measurement errors.

Post-Selection

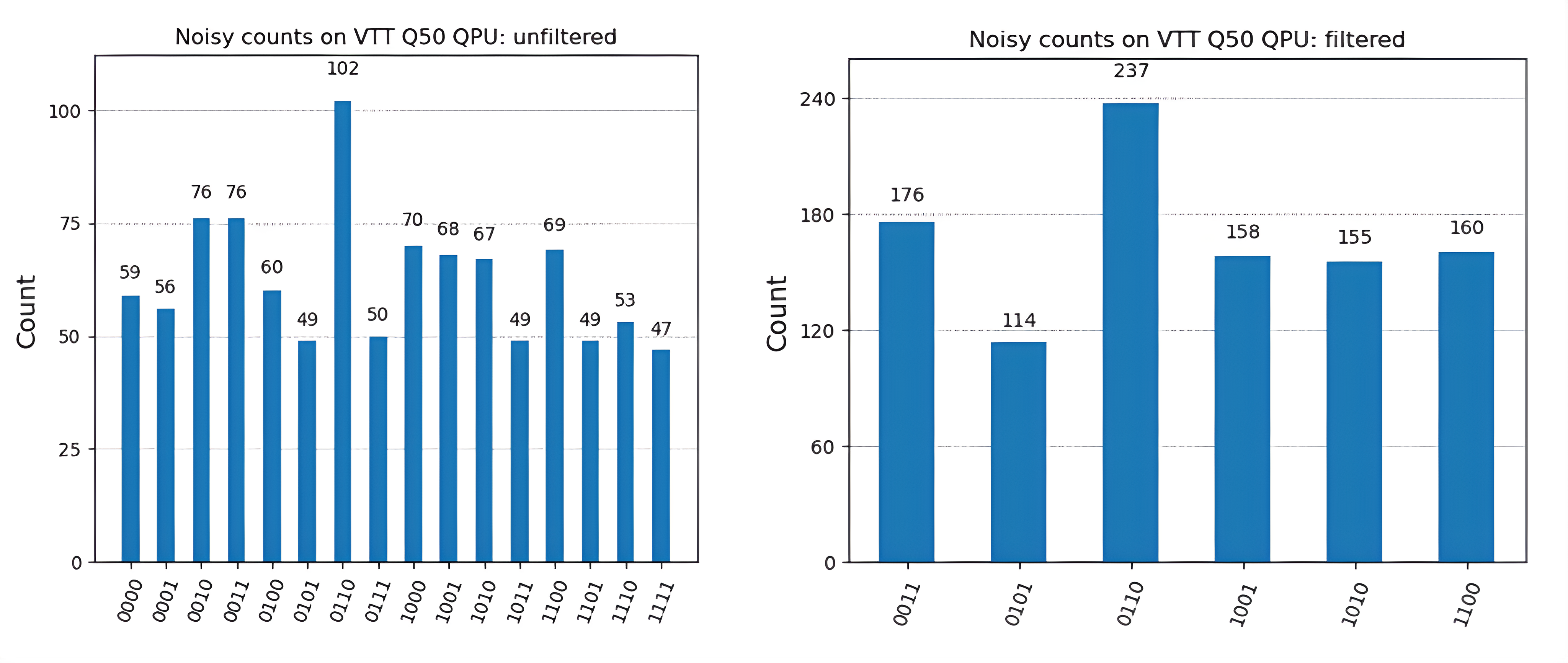

Post-selection is an error mitigation method that can be used when the system of interest has some known symmetry [13]. In the case of the Fermi-Hubbard model, the system is number-preserving and conserves spin. The physically inspired and problem-specific fermionic circuit has been designed so that it respects these symmetries. However, when run on a real quantum computer, the noise from the device causes the measurement results to leak into physically incorrect states, which do not preserve the particle number. This type of error can be mitigated by filtering out the physically incorrect states [13]. The effect of implementing post-selection on the measurement results obtained from the VTT Q50 quantum computer is shown below.

Figure 12: Plot showing the effect of implementing post-selection to results obtained from the VTT Q50 quantum computer. Post-selection has been implemented to the noisy results presented in the previous section.

Readout Error Mitigation

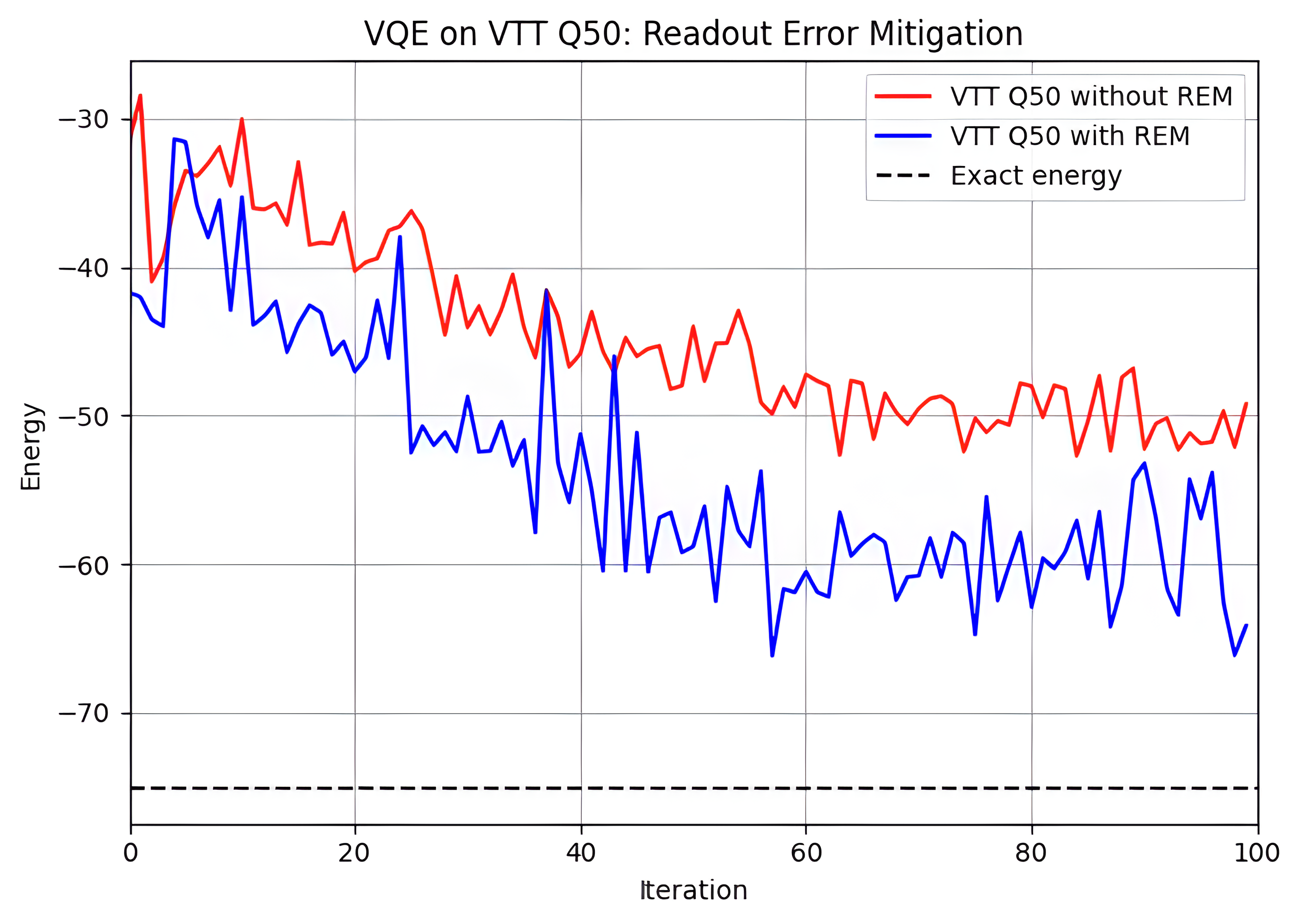

Readout error mitigation (REM) is an error mitigation strategy used to reduce the effect of the noise occurring during the final measurement [7]. Here, readout error mitigation was implemented by first composing and running calibration circuits, generating a mitigation matrix based on the calibration results and finding its inverse matrix. This inverse mitigation matrix was used with the CorrelatedReadoutMitigator from Qiskit Experiments to obtain the mitigated energies. The inverse matrix was also applied to the noisy state counts to obtain the mitigated counts. A Jupyter Notebook with the steps for this can be found here.

Figure 13: A plot of energy convergence results for the ground state energy of the Fermi-Hubbard model obtained from running the algorithm with 6 qubits on the VTT Q50 quantum computer with and without readout error mitigation.

From Figure 13 it can be seen that there is a notable improvement in accuracy when readout error mitigation is used, with the achieved energy being 13 % closer to the true ground state energy. However, the steeper peaks and lows in the mitigated curve show that adding readout error mitigation increases variance, which needs to be accounted for by increasing the number of shots used. We note that active, shot-by-shot readout error mitigation techniques have also been developed that reduce the variance [8]. Further improvement could be achieved by implementing other error mitigation strategies which address noise from two-qubit gates, such as zero noise extrapolation (ZNE) and circuit cutting.

Conclusions

The simulation of quantum systems like electronic models is a challenging task for classical computers due to the associated high computational cost. It is therefore an area where quantum computers are expected to have a big impact. However, in the current era of Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, the number of qubits is limited, and noise poses constraints for circuit depth. Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQEs), a type of hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, have been developed in an attempt to overcome these limitations and gain utility from the currently available quantum computers.

In this project, a VQE workflow has been demonstrated on the hybrid HPC+QC Finnish Quantum-Computing Infrastructure FiQCI. The benchmarking results highlight that in VQE design, a problem-specific parametrized quantum circuit is crucial for obtaining the best performance. Additionally, optimal compilation of the circuit can make a big difference. Finding physically inspired or problem-specific circuits and layouts can be difficult and time-consuming, however. In the future, this is where ML/AI tools are expected to be helpful. In addition to considerations in algorithm design, error mitigation strategies are important to further address limitations posed by noise, especially for larger circuits.

Notebooks

The code for the Fermi-Hubbard VQE for the simulation of electronic systems can be found here. Additionally, a VQE for the Heisenberg model used for simulating magnetic systems but not discussed in this blog post can be found here.

References

-

C. Cade et al., “Strategies for solving the Fermi-Hubbard model on near-term quantum computers”, Phys. Rev. B 102, 235122 (2020) doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.235122

-

M. Stephens, “Gaining a Quantum Advantage Sooner than Expected”, Physics 13 (2020): pp. 159, doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/Physics.13.s159

-

D. Wecker, M. Hastings, N. Wiebe. “Solving strongly correlated electron models on a quantum computer”, Phys. Rev. A 92, 062318 (2015). doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.92.062318

-

A. Kan and B. C. B. Symons. “Resource-optimized fault-tolerant simulation of the Fermi-Hubbard model and high-temperature superconductor models”, npj Quantum 11, 138 (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41534-025-01091-0

-

M. Cerezo, A. Arrasmith, R. Babbush, et al. “Variational quantum algorithms”, Nat Rev Phys 3, pp. 625–644 (2021). doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-021-00348-9

-

Y. Liu, S. Che, J. Zhou, et al. “Fermihedral: On the Optimal Compilation for Fermion-to-Qubit Encoding”, ASPLOS 2024, pp. 382–397(2024). doi: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.17794

-

https://github.com/Qiskit/textbook/blob/main/notebooks/quantum-hardware/measurement-error-mitigation.ipynb [Accessed: Aug. 22 2025]

-

R. Hicks, B. Kobrin, C. Bauer, and B. Nachman. “Active readout-error mitigation”, Phys. Rev. A 105, 012419 (2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.105.012419

-

J. Tilly, H. Chen, S. Cao, et al. “The Variational Quantum Eigensolver: A review of methods and best practices”, Physics Reports 986, pp. 1–128 (2022). doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2022.08.003

-

R. Wiersema, C. Zhou, Y. de Sereville, et al. “Exploring entanglement and optimization within the Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz.” PRX Quan- tum, 1:020319 (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.1.020319

-

L. Bittel and M. Kliesch. “Training variational quantum algorithms is NP-hard”, Physical Review Letters, 127(12) (2021). doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.120502

-

K. Brown, W. Munro, and V. Kendon. “Using quantum computers for quantum simulation”, Entropy, 12(11):2268–2307 (2010). doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/e12112268

-

B. Martin, P. Simon, and M. Rančić. “Simulating strongly interacting Hubbard chains with the variational Hamiltonian ansatz on a quantum computer”, Phys. Rev. Research 4, 023190 (2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.4.023190