“What is dark matter?” is a question that as been asked by scientists for many years. Recently an interest has spiked on using qubits as sensors for finding dark matter. Superconducting qubits are used for searching for a specific type of dark matter particle, an axion. Axions are light particles that do not interact with “ordinary” matter easily. However, they can cause additional electrical currents while coupling to photons which could be sensed by a qubit. These signals are very weak and it has been proposed that the sensitivity of the qubit sensor system could be increased with a quantum circuit. In this blog post, an introduction to the basics of using qubits as sensors and an introduction to axion dark matter is given. The use of superconducting qubits for axion dark matter detection is also motivated and the circuit for the sensitivity enhancement is presented. The code for this circuit is also available so that anyone can run it on the VTT Q50 quantum computer.

Qubits as sensors

Qubits are mostly familiar from their use in quantum computing. However, they have another field of application as well, they can be used as quantum sensors. In quantum sensing, the sensitivity to external disturbances of a quantum system is used to perform measurements [1]. Some important requirements for a quantum system to be used as a sensor are for it to have discrete energy levels, the possibility to initialize, control, and read out the quantum states of the system, and the controllability of the system by an external field. Some examples of quantum sensors are atomic vapor magnetometers, atomic clocks, and qubits. This blog post concentrates on how superconducting qubits can be used as sensors.

Superconducting qubits can be modified to sense electric or magnetic fields trough shifts in energy levels or in resonance frequencies [2]. Transmons, a form of superconducting qubits, consist of an electric circuit with an inductor, capacitor and a so-called Josephson junction. Qubits can be used as single-photon sensors, where signals with higher frequencies that are interacting with electromagnetism can be sensed. Usually, the qubits detect photons by their electric field that scatters on a microwave cavity causing errors in the computation. There is also another technique that has been proposed: the photons could be sensed directly by the qubit getting excited [3,4,5]. Here, a technique for dark matter detection based on the direct excitation of a qubit is presented.

Qubits are an interesting and useful choice to be used as sensors for several reasons. The tuneability of the parameters is good, for example the transition energies and frequencies can be chosen [2]. Qubits are also extremely sensitive to their surroundings. In quantum computing, this is quite the annoyance, but in the field of sensing, this feature can be used to detect low-power signals. One or more qubits can be used in the process [1]. This allows, for example, utilizing the entanglement of qubits, which will increase the sensitivity of the system. An example of this with more details is presented in the section Enhancing the dark matter detection with a quantum circuit.

Detection of dark matter

The ordinary, everyday matter that we observe and interact with daily is composed of particles such as protons and neutrons. According to present understanding, it makes up for only 4% of the universe. Dark matter is significantly more prevalent, with around a 26% share of the composition. The missing part is hypothesized to be dark energy [6].

Dark matter is a hypothetical form of matter that does not interact with ordinary matter or radiation, except through gravity. The exact nature of dark matter is still very much a mystery. As we do not know exactly what it is, its detection becomes rather difficult. However, some theories about its properties have been suggested based on cosmological observations. It is thought that dark matter particles move slower than the speed of light [7]. This type of slow dark matter particles are called cold dark matter. The cold dark matter theory suggests that the particle candidates are weakly interacting. One particle that fits this theory is the axion.

The axion ia a very light particle that comes from a proposed solution for the strong CP problem. The strong CP problem asks why the strong force does not break the symmetry between matter and antimatter [7,8]. The proposed solution involves a force that should give the neutrino, an elementary particle that interacts through the weak interaction and gravity, a very large dipole moment. However, neutrinos are neutral and an electric dipole moment has never been observed.

Considering different symmetries, this leads to the introduction of a new particle: the axion. This adds a new field and a new particle to the Standard Model, a field theory that describes three of the fundamental forces in nature. The axion field would have a value such that the electronic dipole moment of the neutron vanishes [8]. Axion masses are theorized to be in the $\mu eV$ range. These are extremely light particles, for example the electron mass is 0.5 $MeV$. In strong magnetic fields, axions could be converted into photons. This axion-photon coupling could lead to untypical magnetic fields and additional electrical currents [8].

How can dark matter then be detected? The general idea is that if dark matter really is omnipresent in the universe, Earth should be passing through it. By setting up a highly sensitive device, dark matter will hit it at some point and a particle could be detected [7]. This is called direct detection of dark matter particles. Dark matter particles could also be discovered through indirect detection. In this method, the byproducts, of for example an axion coupling into a photon, are being detected. In all cases, these signals are very weak and highly sensitive devices are needed for the measurements. Now, qubits are highly sensitive, controllable, and tunable thus they could be used in these measurements.

One way that a qubit can be used as a dark matter sensor has been presented in [4]. In that paper, an indirect method of dark matter detection is presented. It is a detection of an axion-photon interaction with a transmon qubit. A strong magnetic field is applied around transmon qubits. When an axion encounters this magnetic field it will be converted into a photon. This photon will then interact with the qubit which would induce a measurable state-transition in the qubit. A challenge with this experiment is the magnetic field around the qubit, as it can influence the qubit coherence time. If the magnetic field is correctly aligned and not too strong, the qubit should be fine. In the experiment presented in [4], the magnetic field applied around the qubit has the strength of $5T$. This is magnetic field strength is in the same range as the ones used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines in health care.

If the qubit is hit by the photon from the axion’s interaction with the magnetic field, the qubit will evolve in time according to a unitary evolution [4]. The unitary evolution consist of different parameters related to the assumed mass and density of the axion and of parameters of the qubit itself. The system will be left to evolve for a time $\tau$, which is either the qubit decoherence or the dark matter decoherence time depending on which one is shorter. The dark matter decoherence time is usually estimated as 100 $\mu s$, [4], whereas superconducting qubit decoherence times can be up to a millisecond [9]. The detection probability of the dark matter grows with larger values of $\tau$, thus it would be important to have the experiment running as long as possible [4].

The unitary evolution of the qubit when dark matter hits it can be approximated as:

\[U_{DM} \approx \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\eta\tau) & i e^{-i\alpha} \sin(\eta\tau) \\ i e^{i\alpha} \sin(\eta\tau) & \cos(\eta\tau) \end{pmatrix}\]where $\tau$ is the decoherence time, $\eta$ is a variable containing the the dark matter and qubit properties, and $\alpha$ is a random phase from the axion oscillation [4,5]. However, this unitary can still be further simplified. It can be done by assuming that the qubit and the dark matter frequencies are close to each other and by absorbing the evolution phase $e^{\pm i \alpha}$ into the definition of the excited state of the qubit [4,5]. Now the unitary looks like:

\[U_{DM} \approx \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\eta\tau) & i \sin(\eta\tau) \\ i \sin(\eta\tau) & \cos(\eta\tau) \end{pmatrix}\]The variable $\eta$ can also be opened so that it can be seen what the unitary transformation really is dependent on,

\[\eta = 1/2 \epsilon\kappa d \sqrt(C\omega\rho_{dm})cos\Theta.\]where $\epsilon$ is the kinetic mixing parameter that describes the coupling, $\kappa$ is the package coefficient, $d$ is the effective distance between two conductor plates, $C$ is the capacitance of the conductor, $\omega$ is the energy difference between the ground and excited states of the qubit, $\rho_{dm}$ is the energy density of the dark matter, and $\Theta$ is the angle between the electric field induced by the photon and the normal vector of the capacitor [4,5]. In dark matter search, it is assumed that the energy difference $\omega$ is equal to the mass of the dark matter axion, $m_{dm}$ [5]. Thus the excitation rate is enhanced and the dark matter particles can be observed just by measuring if the qubit has been excited or not. This assumption also means that the qubit frequency is equal to the mass of the axion.

The detection protocol for the experiment presented in [4], includes the following steps:

- First, the qubit is prepared and initialized to the ground state.

- Then, it is left to evolve for time $\tau$

- Finally, the state is measured.

This is repeated as many times as desired and then the whole detection protocol is repeated for a new qubit frequency. The qubit frequency is equal to the axion mass, so in order to scan through the range of possible masses of the axion, the value of the qubit frequency has to be changed to the value of the mass that is wanted to be observed [3,4]. This process is time consuming. Some experiments might take as long as a year to complete all of the measurements. During the measurements, it is assumed that there is the possibility of a readout error and errors coming from thermal excitation [3]. Thus, a signal-to-noise ratio can be calculated to only take into account the signals that are above a certain threshold.

Enhancing the dark matter detection with a quantum circuit

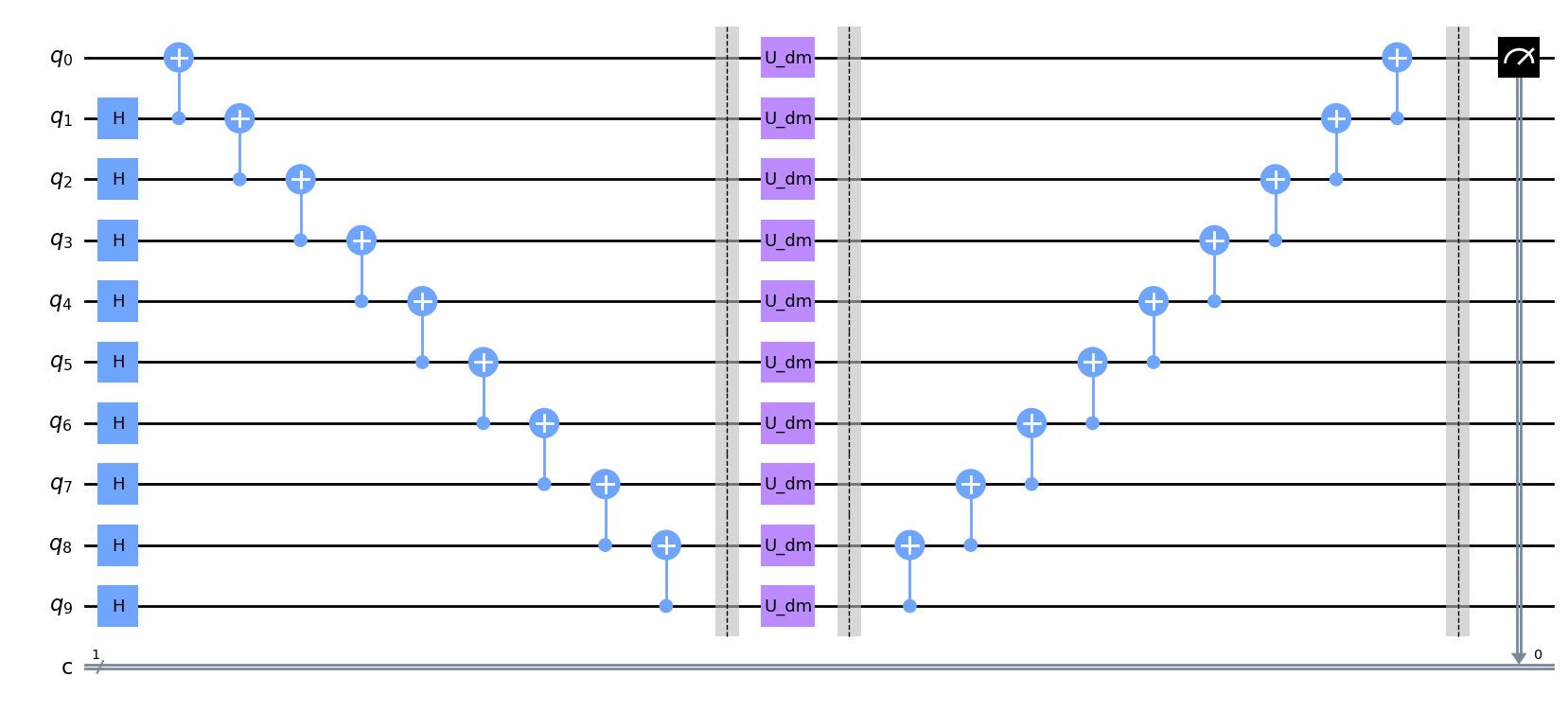

As the signals from dark matter and its interactions are faint, very sensitive devices are needed to observe them. The sensitivity of the qubit sensor can be improved by using entangled qubits [4,5] using Greenberg-Horne-Zeilinger (GHZ) states. The GHZ state works in the following way: first $N$ qubits are initialized into the ground state, then they are put into superposition with a Hadamard gate and entangled by, for example, using CNOT gates [1]. The new state now evolves for a certain time $\tau$ and it picks up a phase, the phase in this case is from the axion-photon interaction, that is enhanced by a factor of $N$, then the superposition state is converted back with more of the same entanglement gates, CNOT gates in this case, and finally the first qubit is read out. The oscillation frequency will increase by a factor of $N$. The noise from the measurement does not increase as only one qubit is measured. Figure 1 shows an example of this kind of a circuit for 10 qubits.

Figure 1: A diagram of the enhancement circuit for the dark matter detection with qubits.

Figure 1: A diagram of the enhancement circuit for the dark matter detection with qubits.

The detection protocol with entangled qubits is similar to the one with only one qubit [4]. The detection is begun by preparing the qubits and initializing them to the ground state. Then they are passed trough the signal enhancement circuit, where the qubits evolve for time $\tau$. In this example the qubits will evolve according to the unitary $U_{DM}$. This cycle is repeated as many times as desired and then the whole protocol is repeated for a qubit frequency that would correspond to a new axion mass. Also these measurements can take a year to complete.

The approach also has some challenges that need to be accounted for. The gate operations used for the enhancement introduce false excitations coming from the gate operation errors [4]. In the experiment presented in [4], the error is assumed to be 0.1% per gate. The coherence time of an entangled system is also lower than for a single qubit. This means that the number of qubits used is bounded by the decoherence time of the dark matter. The decoherence time of the qubit system needs to be longer than the one of the dark matter. These challenges could be solved with improved qubits and quantum computers, and they serve as another important example of why working towards better quantum systems is crucial.

Example of the enhancement circuit with the VTT Q50

The enhancement circuit with the $U_{DM}$ can be run on the VTT Q50 quantum computer to simulate how the circuit works. Dark matter cannot actually be detected as there is too much noise coming from the environment. Furthermore, the qubits in VTT Q50 are designed for quantum computing and not tuned for quantum sensing. The qubits would have to be accompanied by a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), that varies the qubit’s frequency by applying a small external magnetic filed to the qubit, in order to be suitable for the sensing experiment [4]. However, the detection experiment can still be simulated and it can be seen how the signal from the simulated dark matter is enhanced by the GHZ states. In this section, the values used for the $U_{DM}$ and the results from the circuit are presented. The code can be found in Notebooks.

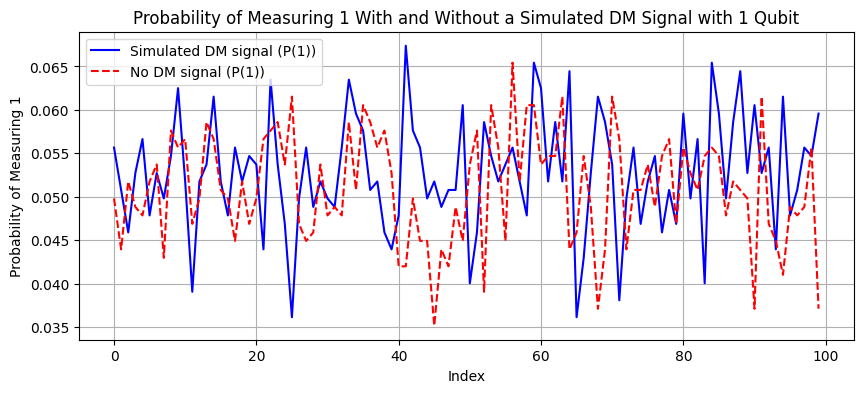

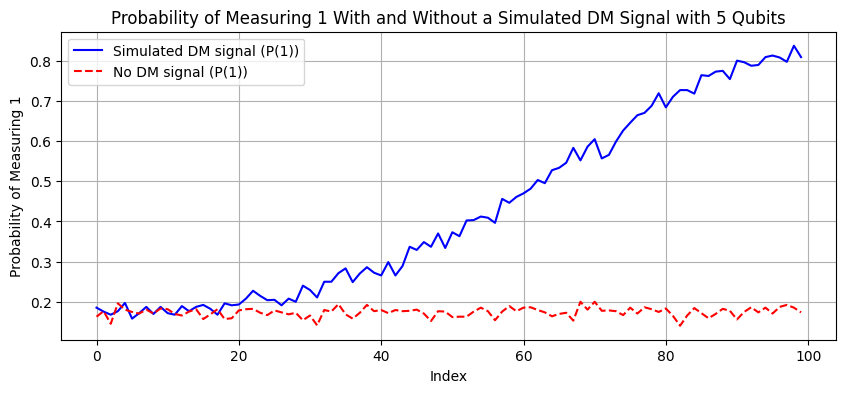

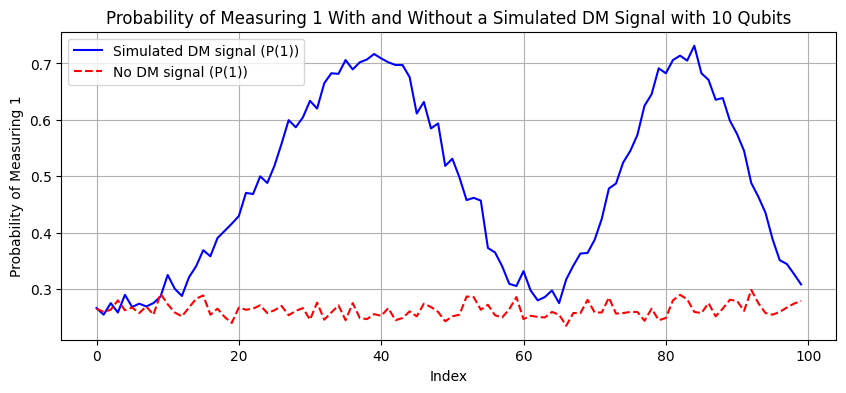

Before running the enhancement circuit with a simulated dark matter signal, it can be run without one to compare later what is the difference made by the dark matter signal to the qubit’s state. The circuit with the absence of dark matter was run with 1, 5, and 10 qubits. These numbers of qubits were chosen in order to test how the absence of a dark matter signal, and later how a simulated dark matter signal, affects a single qubit and how it affects the enhancement circuit. The circuits without the simulated dark matter signal were run on a simulator that mimics the real VTT Q50 quantum computer. The results can be seen in Figure 2.

The signal from the dark matter particle can be simulated by creating a unitary gate that uses the unitary evolution of the qubit presented before. The parameters used for the unitary evolution can be found in Table 1. The parameters used are based on previous research [3,4,5]. The parameter $cos\Theta$ is on average equal to $1/3$ thus the angle $\Theta$ was calculated based on that [3,5]. The package coefficient parameter $\kappa$ from the $U_{DM}$ is also used as the number of qubits. The range of the mass and the kinetic mixing parameter are gone through as lists containing 100 points and each corresponding point is used to calculate a $U_{DM}$. In this example, a linear dependence is assumed between the two parameters. Then the $U_{DM}$ is used in the enhancement circuit. Finally, the probabilities of the first qubit being in the excited state for each mass and kinetic mixing parameter pair are drawn, shown in Figure 2.

Table 1: Parameters of the dark matter and the qubit used for the unitary operator

| Parameter | Value (units) |

|---|---|

| Dark matter mass ($m_{dm}$) range | $10 - 100 \mu eV$ |

| Kinetic mixing parameter ($\epsilon$) range | $10^{-3} - 10$ |

| Capacitance ($C$) | $0.1pF$ |

| Distance between the conductor plates ($d$) | $100 \mu m$ |

| Dark matter density ($\rho$) | $0.45 GeV/cm^3$ |

| Number of qubits / package coefficient ($\kappa$) | 1, 5 or 10 |

| Angle between the electric field and the normal vector of the capacitor ($\Theta$) | 54.74° |

| Decoherence time ($\tau$) | $100 \mu s$ |

The circuits without the simulated dark matter signal were run 100 times to match the experiment with the simulated dark matter signal. The graphs in Figure 2 show the probability of the first qubit being in the excited state after each run. The index of the run also corresponds to the index of the axion parameters used, i.e. which mass and kinetic mixing parameter was used in $U_{DM}$. Furthermore, Figure 2 shows the difference between running the circuits with 1, 5, and 10 qubits and the difference in running the circuit with and without a simulated dark matter signal.

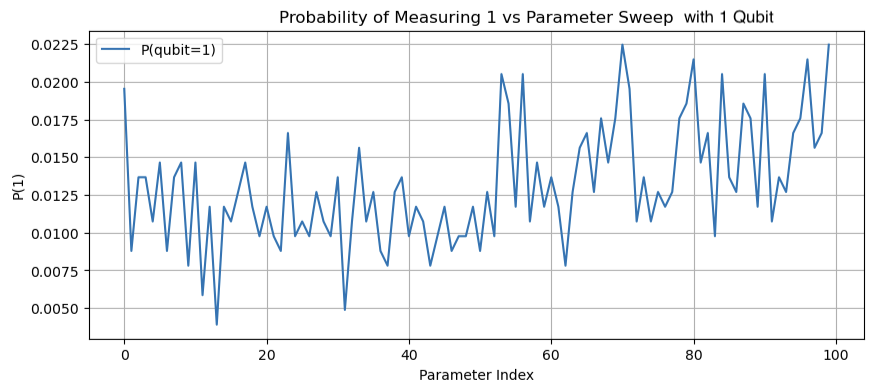

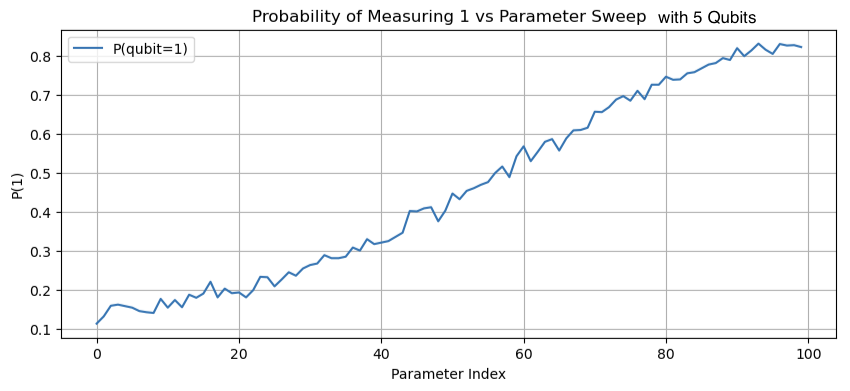

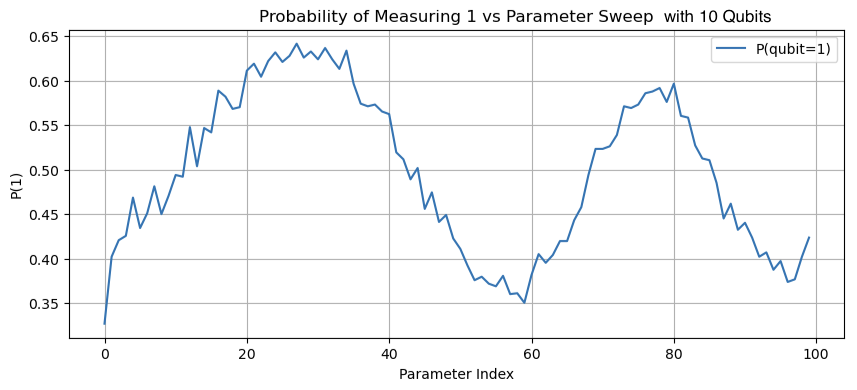

In Figure 2, the circuits with the simulated dark matter signal were also run on a simulator that mimics the VTT Q50 quantum computer. Figure 3 shows the probabilities of a qubit being in an excited state after a simulated dark matter signal is applied. The circuits were run with 1, 5 and 10 qubits. This time the circuits were run on the actual VTT Q50 quantum computer.

Figure 2: Probability of a qubit being in an excited state with and without $U_{DM}$ acting on it. The circuits have 1, 5, and 10 qubits respectively and were run on a simulator mimicking the VTT Q50 quantum computer. The dashed red line is the experiment without the simulated dark matter signal. The blue line is the experiment with the simulated dark matter signal.

For the experiment without a simulated dark matter signal in Figure 2, it can be seen that with one qubit there is small fluctuations coming from noise but the qubit is not getting excited. With 5 and 10 qubits the fluctuations become larger, this is most likely due to more noise being introduced by the gates that are used in the enhancement circuit and not in the one qubit version. Thus, without the simulated dark matter signal everything that is seen from this experiment is noise. From the results of the enhancement circuits with the simulated dark matter signal, Figure 2 and Figure 3, periodic signals that do not blend into the noise can be seen.

The experiments with the simulated dark matter signal in Figure 2 show that even with a rather low number of qubits, a clear improvement can be observed in the probabilities of the qubit being in an excited state. This makes observation of a dark matter particle easier. With the entangled circuit that has multiple qubits as sensors, a bigger range of dark matter particles with different masses and kinetic mixing parameters can be seen exciting the qubit. This means that the probability of observing an axion in the whole possible mass range is more likely than with a single qubit as the sensor. There are some constraints for the mass and kinetic mixing parameter coming from cosmological and astrophysical models and from existing dark matter search results, [4], that have not been accounted for in this example. Thus, some of the mass and kinetic mixing parameters used in this sweep might not make physically sense even if they are shown to be probable to observe in the results from the circuit.

Figure 3: Probability of a qubit being in an excited state after $U_{DM}$ has acted on it. The circuits have 1, 5, and 10 qubits respectively and were run on the VTT Q50 quantum computer.

Comparing the results of the enhancement circuits run with the simulator to the enhancement circuits that have been run on the VTT Q50 quantum computer in Figure 3, similar probability plots can be seen. The probability of the qubit being in state 1 has increased and the signals from a larger range can be observed. However, the amount of noise has increased when simulating the axion dark matter detection experiment on a real quantum computer. Because of the noise, the enhancement is not as good as on the simulator but the probability of excitation is still considerably higher than in the one-qubit circuit and the signal can be recognized and it does not blend into the noise.

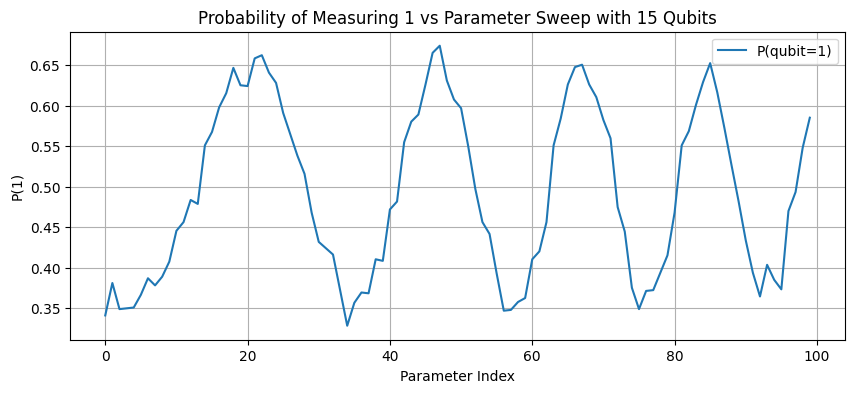

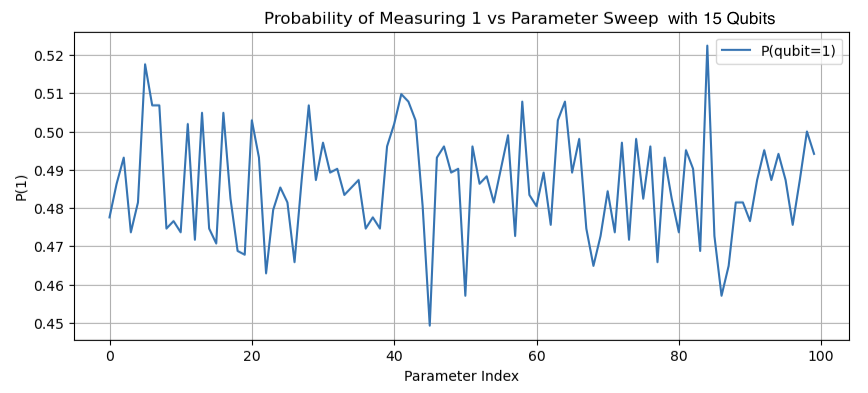

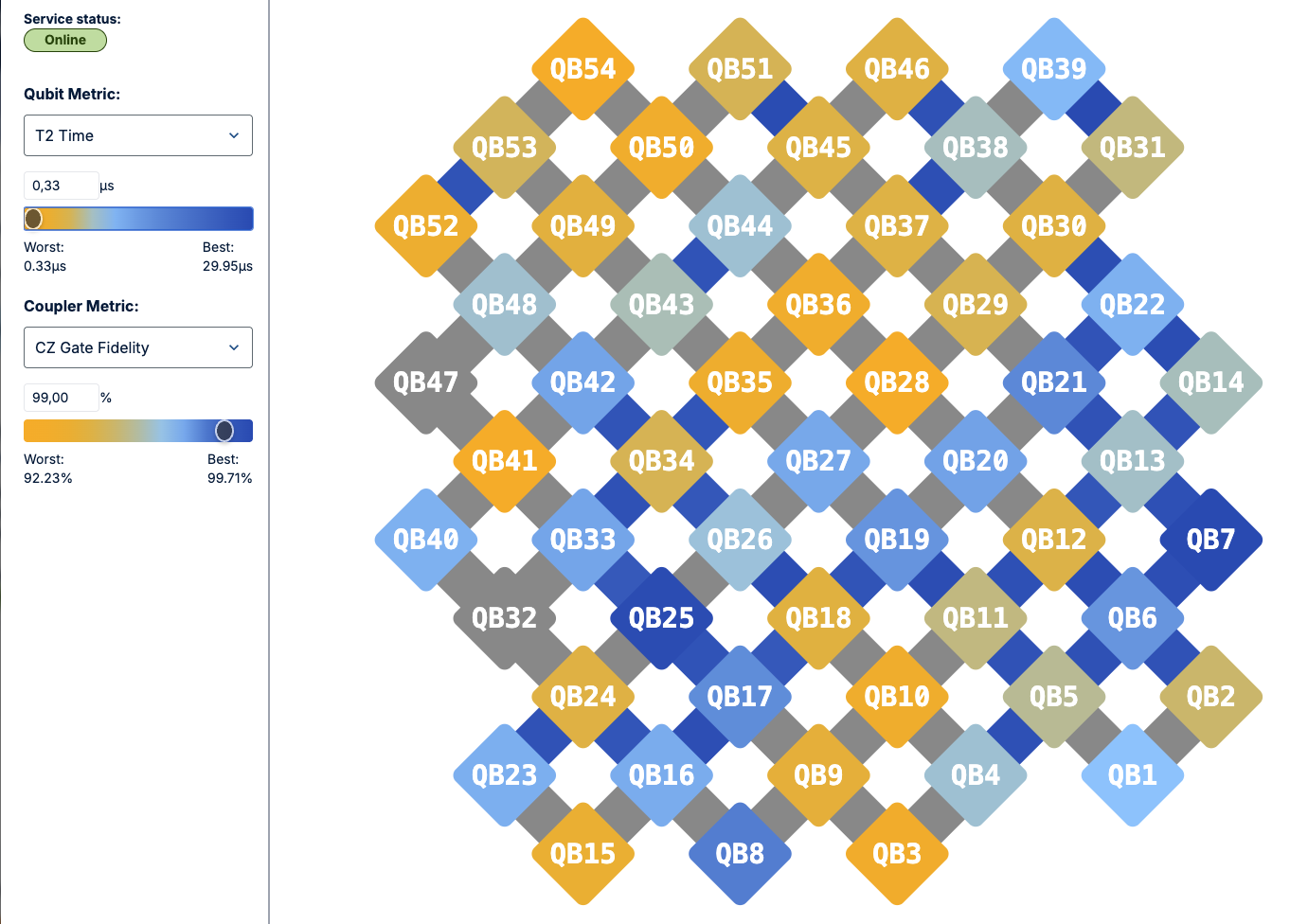

In Figure 4, the enhancement circuit was run with 15 qubits on the simulator mimicking VTT Q50 and the VTT Q50 quantum computer. These results show that on the real quantum computer the noise increases quickly with the number of gates in the quantum circuit, blending the dark matter signal into the noise. These results could be improved by choosing qubits that have low error rates and good couplers between them. This is possible by checking the layout of the VTT Q50 quantum computer with overlaid calibration data from the FiQCI website. The calibration map at the time when the circuits were run is in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Probability of a qubit being in an excited state after $U_{DM}$ has acted on it. The circuit has 15 qubits and was run on the simulator mimicking VTT Q50 and the real VTT Q50 quantum computer respectively.

Figure 5: The layout of the VTT Q50 quantum computer with overlaid calibration data on the 31st of July 2025, the date of the experiment. This graph can be found form the VTT Q50 layout section on the FiQCI website.

Conclusions

The universe is thought to consist largely of dark matter, with ordinary matter making up a much smaller portion. Thus, understanding the nature of dark matter is crucial for understanding the universe. A candidate for dark matter is a small particle called the axion. Sensing of axions, and dark matter in general, is difficult because of weak signals and almost zero interaction with ordinary matter. This necessitates highly sensitive detection devices. Qubits are very sensitive to their surrounding environment and have therefore been proposed to be used for axion detection. The detection would be based on the excitation of the qubit.

The sensitivity of the qubits for axion detection could be increased with a quantum circuit. The enhancement would be done by amplifying the axion particle’s signal. This allows signals from a broader range of possible axion properties to be detected.

After simulating the axion detection experiment on a real quantum computer, it can be seen that the enhancement circuit does work. The probabilities of the axions exciting the qubits, i.e., being observed, increase. Examples like this one showcase the usefulness of quantum computers beyond computing applications. Improving qubits and quantum computers could have a major impact on solving problems across a wide range of research fields beyond computer science and modelling applications.

Notebooks

The code for the sensitivity enhancement circuit can be found here.

References

-

C. L. Degen, F. Reinhard, and P. Cappellaro, “Quantum sensing,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.02427, June 2017. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.02427

-

A. Chou, K. Irwin, R. H. Maruyama, O. K. Baker, C. Bartram, K. K. Berggren, G. Cancelo, D. Carney, C. L. Chang, H.-M. Cho, M. Garcia‑Sciveres, P. W. Graham et al., “Quantum Sensors for High Energy Physics,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.01930, Nov. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.01930

-

S. Chen, H. Fukuda, T. Inada, T. Moroi, T. Nitta, and T. Sichanugrist, “Detection of hidden photon dark matter using the direct excitation of transmon qubits,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.03884, Dec. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.03884

-

S. Chen, H. Fukuda, T. Inada, T. Moroi, T. Nitta, and T. Sichanugrist, “Search for QCD axion dark matter with transmon qubits and quantum circuit,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19755, Jul. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.19755

-

S. Chen, H. Fukuda, T. Inada, T. Moroi, T. Nitta, and T. Sichanugrist, “Quantum enhancement in dark matter detection with quantum computation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10413, revised Jul. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.10413

-

S. Profumo, “An introduction to particle dark matter,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.05610, Oct. 2019. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.05610

-

B. R. Garrett and D. E. McKay, “Dark matter: A primer,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1006.2483, Jan. 2011. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1006.2483

-

Chadha-Day, F., Ellis, J., and Marsh, D. J. E., “Axion dark matter: What is it and why now?”, Science Advances, vol. 8, no. 8, Art. no. eabj3618, 2022. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abj3618

-

M. Tuokkola, Y. Sunada, H. Kivijärvi, et al., “Methods to achieve near‑millisecond energy relaxation and dephasing times for a superconducting transmon qubit,” Nat. Commun., vol. 16, art. nr. 5421, Jul. 8, 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41467‑025‑61126‑0

-

https://images.nasa.gov/details/webb_first_deep_field (Accessed 15.08.2025)